Bear Obstructive Hydrocephalus

Home » Veterinarians » Case Studies » Bear

History

Bear, a 7-year-old neutered male Wheaten Terrier, presented to Southeast Veterinary Neurology (SEVN) in August of 2020 laterally recumbent and minimally responsive. Prior to presentation, Bear was hospitalized at a pet emergency center with dull mentation, nystagmus, and fever. Despite supportive care, he continued to decline and was referred for neurologic evaluation.

Examination

Upon examination, Bear exhibited a stuporous mentation (unresponsive until a painful stimulus is applied).

Cranial nerve assessment noted spontaneous horizontal nystagmus with fast phase to the right (abnormal horizontal movement of the eye, darting to the right). However, when the position of his head was changed, the nystagmus changed to vertical and rotary. He had an enophthalmos (sunken in eye), and a positional ventral strabismus (abnormal downward position of the eye when the head was raised) was observed in his left eye.

Lastly, Bear was in pain along his cranial cervical spine when palpated.

Based on his examination, Bear’s neuroanatomical localization (where in the nervous system the problem is located) was the central vestibular system (balance system), or the brainstem. This is the location of the reticular activating system, which is very important for waking up the forebrain, i.e. consciousness.

Diagnosis

Bear’s X-rays indicated bilateral cranioventral alveolar infiltrate (fluid in the lungs), worse on the left side than the right, consistent with bronchopneumonia.

In order to evaluate his brain, MRI was performed by SEVN. The MRI showed a mass along the bottom of his brainstem, which was causing significant swelling within the brainstem. The swelling was causing an obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), called obstructive hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus is a buildup of CSF in the brain. In Bear’s case, this was causing an elevation in intracranial pressure (pressure in the skull), which then affects perfusion of the brain (blood flow to the brain).

His CSF analysis showed a marked neutrophilic pleocytosis (increase in white blood cells, specifically neutrophils). This can be seen with tumors called meningiomas, though can also be seen with infectious diseases.

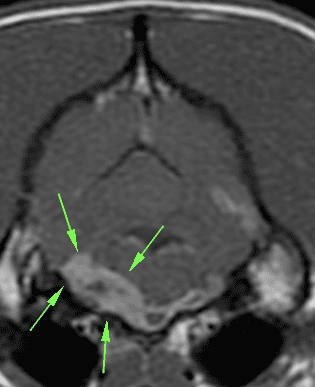

Transverse T1 postcontrast image at the level of the brainstem. The arrows are outlining the bulk of the mass along the left ventral aspect of the brainstem, but it extends to the right side.

Treatment

SEVN surgically placed ventriculosubcutaneous shunts (tubes that redirect CSF to another part of the body for reabsorption) into Bear’s lateral ventricles (chambers in the brain that contain CSF) to allow CSF to drain into the space under the skin at the top of his neck. This was a temporary solution to immediately alleviate intracranial pressure in order to stabilize him and formulate a treatment plan for the mass. He also prescribed steroids to reduce the inflammation within the brainstem caused by the mass.

Bear recovered well after surgery, and was able to walk out the door at the time of discharge, three days later. After discharge, infectious disease testing of his CSF came back negative for all diseases tested, which suggested the mass in his brainstem was cancerous. Bear began radiation therapy at a cancer center. His condition dramatically improved following treatment, and he continued to do great over the next few months.

Unfortunately, by January, he was presenting to SEVN again for disorientation, incoordination, and collapse. A repeat MRI confirmed that his brainstem mass was, in fact, shrinking. However, the MRI also identified enlargement of the entire ventricular system, meaning CSF was building up in the brain again. Since no obvious obstruction was observed, the cause of hydrocephalus was unclear. This implied that the temporary shunts had failed, but that shunts were still necessary.

So this time, Bear was treated with a more permanent solution. In a second surgery, SEVN placed ventriculoperitoneal shunts to divert excess CSF from his brain into his abdomen. Additionally, a suboccipital decompression (a procedure removing part of the back of the skull) was performed to remove any obstruction that may have been restricting the flow of CSF.

During surgery, very little spinal fluid was produced upon initially opening the meninges (membranes that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord). A thin layer of abnormal tissue was discovered at the base of the cerebellum (back part of brain) at the cerebellomedullary cistern. This may have been scar tissue from the mass or radiation, and upon its removal, the spinal fluid was readily flowing through the area.

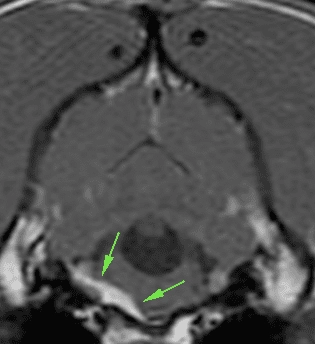

Transverse T1 postcontrast image at the level of the brainstem, 17 months later. The mass is much reduced in size. The fourth ventricle is dilated, and the ventricular catheters are visible within the soft tissues dorsal to the skull.

This did the trick, and Bear has been doing fantastic ever since. At all of his subsequent rechecks, he was bright and alert with normal mentation, ambulatory with no signs of weakness, and not in any pain. His only remaining clinical sign was a subtle menace response deficit in his right eye. Other than that, he has been neurologically normal and back to his normal happy self at home.

Takeaway

Hydrocephalus is a buildup of CSF in the brain. In Bear’s case, the hydrocephalus developed because of a mass that was obstructing the normal flow of fluid through the nervous system. Temporary shunts helped stabilize him to allow for treatment of the tumor. Over time the shunts failed, and he developed a membrane that caused the obstructive hydrocephalus to persist. This could have formed due to inflammation related to the mass, radiation, or some other disease process.

The excess fluid was compromising blood supply to the brain, which can cause rapidly progressive changes in mentation. If left untreated, hydrocephalus can be fatal. While the temporary shunts provided stabilization, the permanent shunts have pressure valves to more precisely regulate the amount of fluid that is removed from the brain.